Reading Between the Lines: The Symbolism of Mid-Century Architecture

- Jun 6, 2023

- 8 min read

In the golden era of design, a movement emerged that forever reshaped the landscape of architecture and aesthetics. Mid-century design, with its clean lines, organic forms, and iconic structures, captured the spirit of innovation and optimism that characterized post-war society. As we delve into the hidden symbolism and timeless allure of this design movement, we uncover a world of artistic expression and a language of shapes and patterns that continues to inspire us today. Join us on a journey as we explore the captivating history and symbolism behind the iconic architectural treasures of the mid-century era, and discover how Oliver Peoples' Mid-Century inspired filigree designs reflect this profound connection.

The Tramway Gas Station (now the Palm Springs Visitor Center). Photo by Bill Anderson.

In this realm of hidden narratives, Oliver Peoples stands apart as a brand that forgoes logos to get its point across. Instead, it has incorporated key signifiers that indicate consumers are holding frames from the brand. One of the most important of these signifiers is the brands' use of intricate filigree work. Drawing inspiration from the iconic landmarks of Southern California, these delicate jewelry-like details not only recount the brand's own story but also pay homage to Hollywood's rich heritage. Though often unnoticed, these elevated filigree motifs also mirror the concealed intricacies found within the city's iconic landmarks, inviting us to uncover their enigmatic stories.

The Birth of Mid-Century Design:

Mid-century design, born in the aftermath of World War II, met the demand for functional and affordable homes for the middle class. Drawing inspiration from Scandinavian simplicity and modernist principles, architects and designers crafted a visual language that defined an entire era. At its heart, mid-century design weaves a tapestry of symbolism into its architectural marvels, where sweeping lines and playful geometry tell captivating stories, embodying the spirit of the time and the aspirations of its creators.

John Lautner's 'Elrod House.' Photo by Leland Y. Lee.

Mid-century buildings captivate with their open layouts and expansive windows, forging a sense of freedom and connection to the world outside. But what sets them apart is the meticulous attention to detail found in every nook and cranny. Ornamental screens, textured wall panels, bespoke millwork—the intricate craftsmanship adorns these structures, revealing a harmonious fusion of grandeur and meticulousness.

This emphasis on intricate detailing serves multiple purposes. It adds a layer of visual interest and texture, transforming the overall aesthetic into something captivating and distinct. The interplay of light and shadow on these intricately designed surfaces creates depth and dimension, enhancing the visual experience. Each detail, from ornate door handles to intricately patterned tiles, contributes to the building's narrative, inviting occupants and visitors to explore and appreciate the finer nuances of the design. It is a testament to the designers' ability to strike a balance between openness and intimacy, simplicity and complexity, ultimately leaving an indelible impression on those who encounter these mid-century architectural treasures.

The 'Oliver' & 'Oliver Sun' Frames are pictured below. Both feature

the mid-century filigree. (Photo Courtesy Oliver Peoples.)

The Language of Symbolism:

Mid-century architecture is renowned for its distinctive design motifs and symbolic icons that define the style. Similarly, Oliver peoples has incorporated the mid-century filigree work into three frames that best embody this motif - including the 'Oliver', 'Oliver Sun', and 'Davri' styles.

Shapes also play a significant role in the symbolism of mid-century architecture, as they are often purposefully selected to convey specific meanings and evoke particular emotions. From geometric forms to organic curves, these shapes contribute to the overall aesthetic and conceptual framework of the architectural style:

THE SQUARE: One of the most prevalent shapes in mid-century architecture is the rectangle or square. These shapes represent stability, order, and rationality. They are often used as the fundamental building blocks, defining the structure and layout of the buildings. Rectangular forms create a sense of balance and harmony, emphasizing the functional aspect of the design while maintaining a clean and minimalist aesthetic. In mid-century architecture, squares and rectangles were utilized in both structural and decorative elements. From building facades to windows, doors, and interior partitions, these shapes were employed to create a sense of uniformity, efficiency, and functional clarity. The clean, angular lines of squares and rectangles helped define spaces and provided a sense of visual cohesion. The square and rectangle also symbolized the mid-century movement's focus on rationality and the integration of indoor and outdoor living. Large glass windows and sliding doors, often framed in squares or rectangles, connected interior spaces with the surrounding environment, blurring the boundaries between indoors and outdoors. This integration represented a desire to harmonize with nature while embracing technological progress.

THE CIRCLE: Another common shape seen in mid-century architecture is the circle. Circles symbolize unity, continuity, and infinity. They evoke a sense of harmony and completeness, offering a contrast to the straight lines and sharp angles found in other elements of the design. Circular forms, such as rounded windows or curved walls, soften the overall composition and create a more organic and flowing experience within the space. One notable mid-century architectural detail that prominently features circles is the sunburst or starburst motif. This iconic design element became popular during the mid-20th century and can be seen adorning various architectural structures, furnishings, and decorative objects of the era. The sunburst motif typically consists of radiating lines or spokes emanating from a central circular element, resembling the rays of the sun. This motif symbolizes energy, optimism, and a celebration of the Space Age era that characterized mid-century design. It embodies the spirit of progress, technological advancements, and the exploration of new frontiers that captivated the imagination of designers and architects during that time. The sunburst motif's association with mid-century design can be traced back to its roots in the Art Deco movement of the 1920s and '30s (Sunset Tower hotel, anyone?) which embraced geometric forms and stylized representations of natural elements. However, it gained renewed popularity and evolved during the mid-century period, incorporating cleaner lines and a more streamlined aesthetic.

THE TRIANGLE: Triangular shapes also find their place in mid-century architecture, often representing energy, dynamism, and movement. These shapes can be seen in rooflines, canopies, and angular details. Triangles introduce an element of visual interest and add a touch of playfulness to the overall design. They convey a sense of progress and forward-thinking, reflecting the optimism and innovation of the mid-century era. Triangular rooflines, sometimes referred to as butterfly roofs, shed water efficiently while creating unique silhouettes that became synonymous with mid-century design. The use of triangles in mid-century architecture also reflected the movement's inclination towards organic and natural forms. Inspired by the surrounding landscape, architects sought to blend their designs with nature, and triangles were employed to mimic the shapes found in mountains, hills, and rock formations. The upward-pointing triangle, in particular, symbolized aspiration, growth, and progress, embodying the optimistic spirit of the mid-century era. Furthermore, triangles were often associated with movement and directionality. Their angular lines created a sense of visual tension and implied movement, adding a dynamic quality to the architectural composition. This symbolism aligned with the mid-century era's fascination with speed, efficiency, and the emerging automobile culture.

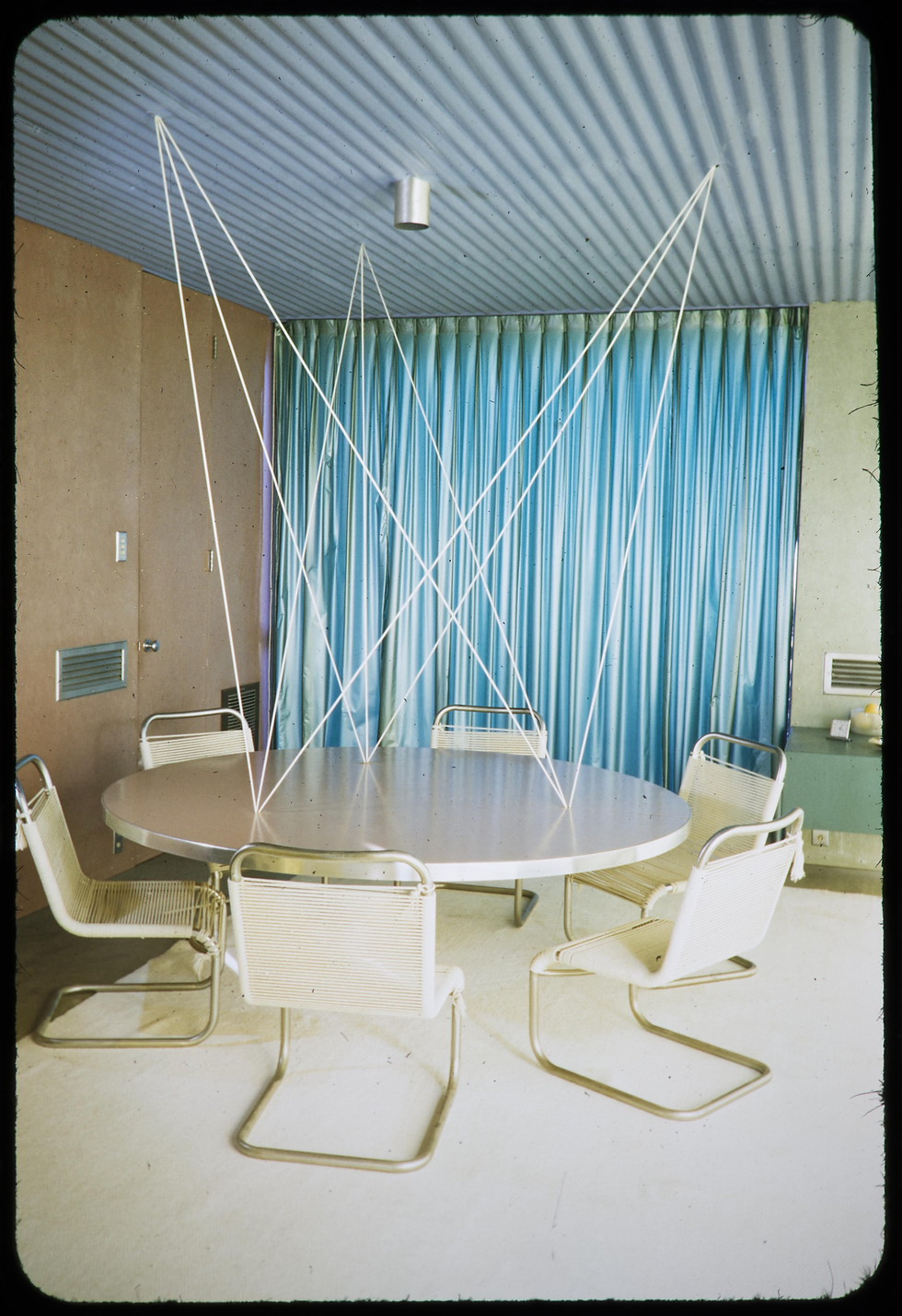

The Suspended dining table at the Frey House. (Photo: USC Archives)

Perfectly Imperfect: Additionally, mid-century architecture embraces asymmetrical compositions, which challenge the traditional notion of symmetry and balance. Asymmetry can convey a sense of creativity, individuality, and non-conformity. It breaks away from the strict formalities of earlier architectural styles and adds an element of surprise and excitement to the design.

These asymmetrical elements can be seen in features such as cantilevered balconies, irregularly shaped windows, or off-center entrances. Beyond specific shapes, mid-century architecture often incorporates abstract and sculptural forms. These shapes have a more subjective interpretation, allowing viewers to find their own meaning and connection through the interplay of natural and manmade forms. Organic, amoeba-like shapes might evoke a sense of nature and fluidity, while angular and sharp forms could represent the influence of technology and progress.

The Kaufman House by Richard Neutra. (Photo by Julius Shulman)

Art Imitating life:

Armed with a new understanding of the language of symbolism; the striking similarities between these popular Mid-Century design motifs and the geometric details featured in the Oliver People's logo become harder to ignore. The shapes and symbols found in Mid-Century design represent a departure from traditional styles, embracing innovation, simplicity, and a forward-thinking mindset. Whether it's the stability and order evoked by rectangles, the harmony and unity conveyed by circles, the dynamic energy exuded by triangles, or the expressive nature of abstract forms, these shapes all play a pivotal role in shaping the narrative of both design and experience.

This symbolism goes beyond mere aesthetics, inviting all of those with eyes to see to engage with the designs on intellectual and emotional levels, unraveling the layers of meaning behind each element. This interplay of shapes and symbols establishes a profound connection to the Oliver Peoples brand, forging an unspoken alliance between architectural styles and that of the brand's philosophy. This fusion not only celebrates the legacy of design itself, but also underscores the enduring appeal and relevance of symbolism and its principles.

So, the next time you admire the ornate filigree work featured on each pair of Oliver Peoples frames, or stroll past a shining architectural example as you go on about your daily life, we encourage you to take a moment to read between the lines and uncover the rich history and symbolism that may lie just beyond the surface of what we see.

By uncovering and honoring the spirit of past, we become ambassadors to help usher in the future and carry with us the timeless shared language of art, design, beauty, and balance. Discover more

GALLERY

Pic 1: the John Lautner-designed Elrod House. An example of what Lautner called “free architecture,” the house is meant to seamlessly connect with its natural surroundings. To that point - when the house was being built, rocks on the site were left intact so that they became part of the structure. Photo by Leland Y. Lee.

Pic 2: the Kaufmann House by Richard Neutra. A true standout among the houses that came to define Palm Springs as a modern architectural oasis, it was built in 1946 for department store owner Edgar J. Kaufman. Photo by Julius Shulman.

Pic 3: the creative team at Oliver Peoples drew upon various memories and vignettes around Palm Springs in designing the Mid-Century Filigree.

Pic 4: the Tramway Gas Station! Originally built as an Enco gas station, the structure has greeted visitors coming in on Route 111 since 1965. Today it is the Palm Springs Visitor Center and located right at the turnoff for the PS Aerial Tramway. Photo by Bill Anderson.

Pic 5: Oliver Peoples’ mid-century filigree pulls inspiration from the angles found in the mid-century modern architecture of Palm Springs as well as the forms visible throughout the surrounding mountain and desert landscapes.

Pic 6: the suspended dining table at Frey House I. Built in the 40s by architect Albert Frey, the house was torn down by its second owner (a developer who ended up going bankrupt) so now we only have photos - and of course Albert Frey’s second home - Frey House II! Photo from the USC Archives.

Pic 7: Oliver Peoples’ Mid-Century Filigree as seen on their vintage-inspired Oliver, Oliver Sun, and Davri frames.

Disclaimer: The following is a sponsored post from one of our paid partners. In accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising", we hereby disclose that have received monetary compensation as well as complimentary products in association with this post. We do not, however, receive any commissions should you decide to purchase products from the merchant. For more information regarding the merchant, its online store, its privacy policies, and/or any additional terms and conditions that may apply, visit the merchant’s website and click on its information links or contact the merchant directly.

Comments